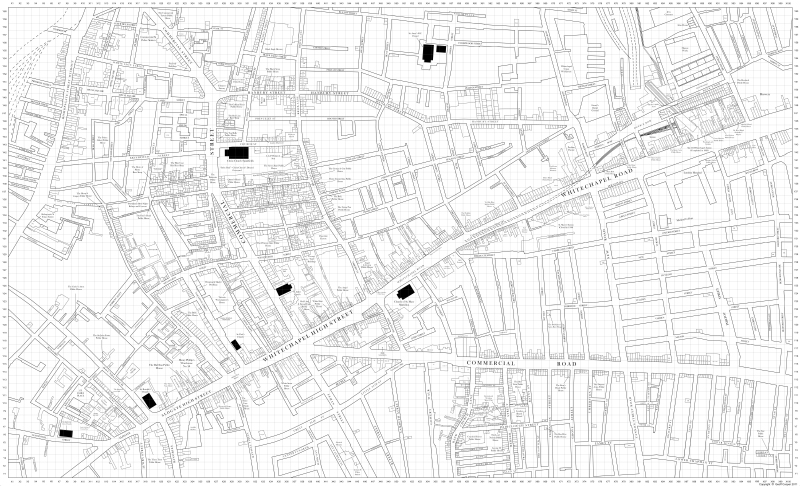

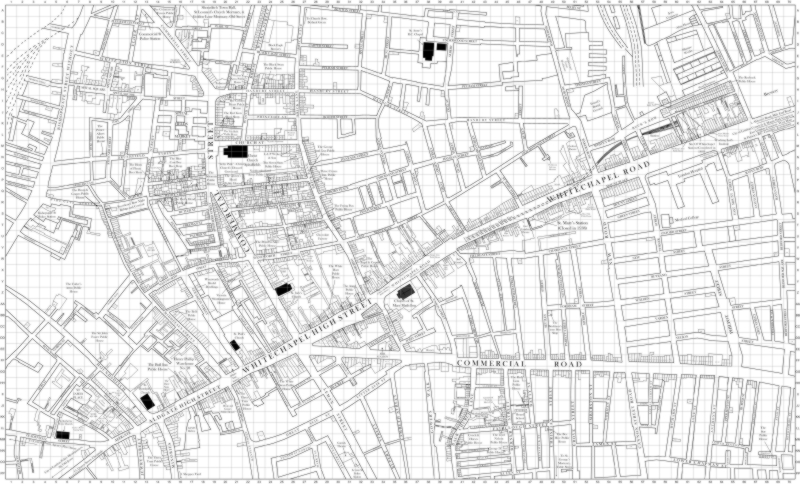

1888 period Maps of London’s East End

Welcome to the Jack the Ripper Map website. Breakthrough research and the latest technology has enabled us to produce the ultimate period maps of the East End of 1888 London. The extraordinary detail shown on these maps gives a complete picture of Jack the Ripper’s killing fields.

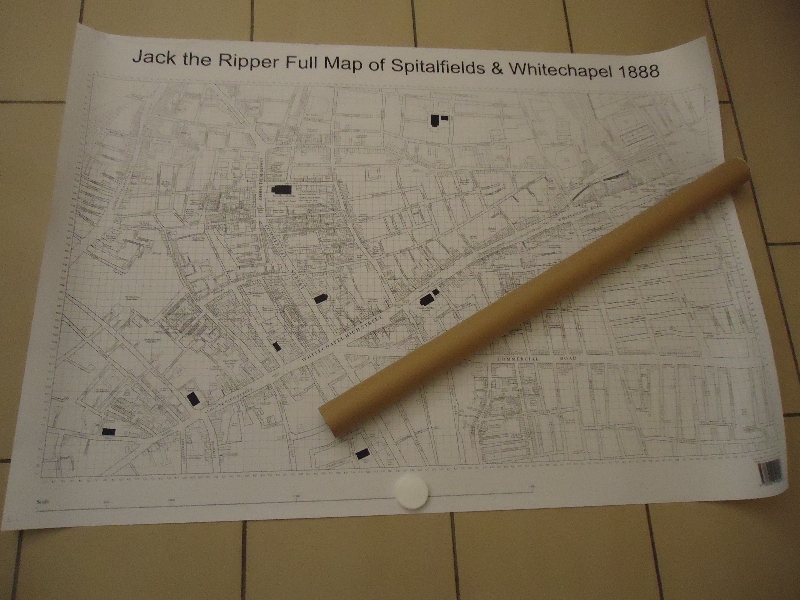

The Jack the Ripper Rolled Up Map of Spitalfields & Whitechapel 1888: ISBN 978-0-9571990-2-6 is no longer available.

The detail on both versions of the map is identical. The accompanying information and the print format is different for each version.

Jack the Ripper Map Book of Spitalfields and Whitechapel 1888, ISBN 978-0-9571990-0-2

The Map Book is No longer available

We are not restricting our research to the ‘Canonical 5’ (sic) murders, but include all possible Jack the Ripper murder victims, also commonly known as the Whitechapel murders, for which we have mappable data.

The images shown here are low resolution versions of the latest maps of the East End of London from 1888, the time period when Jack the Ripper terrorised London, it’s not possible to show the full resolution, as they wouldn’t fit on the screen.

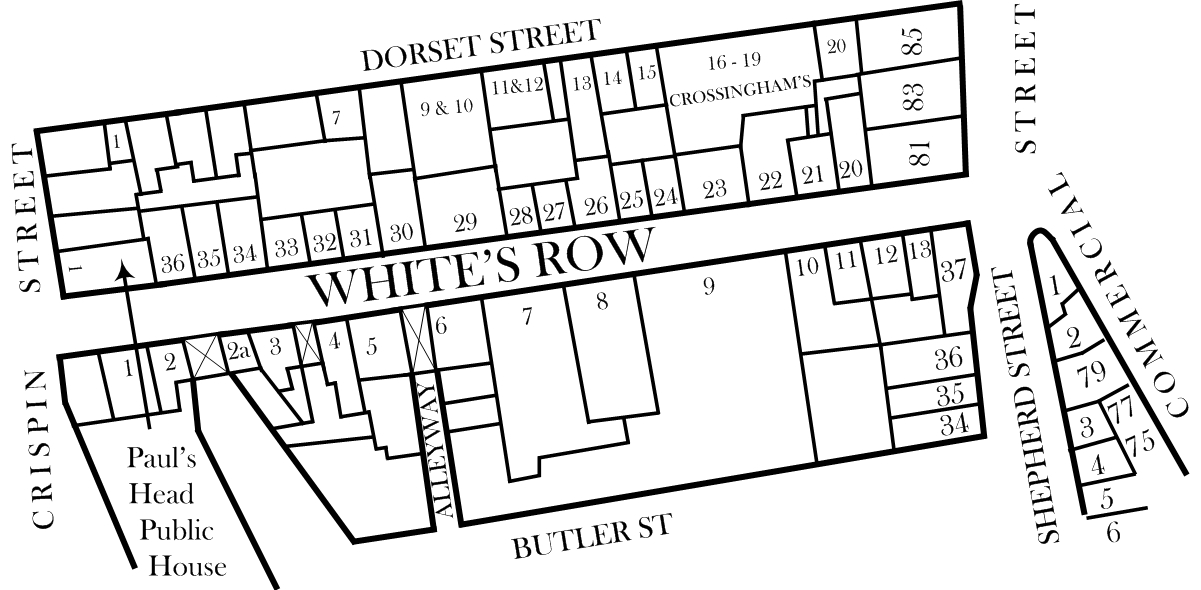

Here’s a full resolution example of the level of detail shown in the new map:

These are highly detailed maps, showing more information than any previous maps ever produced. They include house numbers extracted from the 1881 and 1891 census returns, and doss houses, shops and public houses and other instaitutions are also shown.

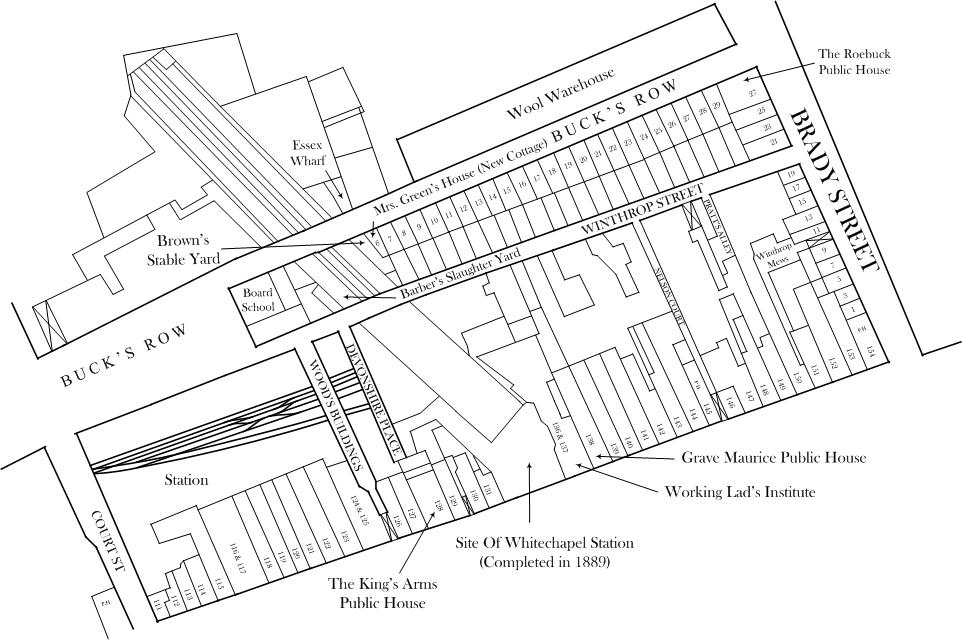

The book also includes enlargements of each of the locations where 10 of the possible Jack the Ripper murder victims lived and died.

The History of Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper is the most notorious serial killer in history. 1888 was a time when the general populace was bocoming increasing more literate and the press seized any opportunity to print a gruesome story in order to sell more newspapers. It has even been rumoured that the name ‘Jack the Ripper’ was invented by a journalist eager to fuel the story.

There were a total of about 11 murders in the Whitechapel area between 1888 and 1889, but the modus operandi differed quite widely between most of them. The ‘Canonical Five’ murders attributed to Jack the Ripper all have similar MO’s, starting with fairly mild mutilation and increasing in ferocity until the 5th murder, when it is generally considered that his reign of terror was over.

The 1st of the Canonical 5 Murders

At about 3.40am on the 31st of August 1888, when a carman named Charles Cross was making his way along Bucks Row Whitechapel, He discerned on the opposite side something lying against the gateway, but he could not at first make out what it was. He thought it was a tarpaulin sheet. He walked into the middle of the road, and saw that it was the figure of a woman. He then heard the footsteps of a man going up Buck’s-row, about forty yards away, in the direction that he himself had come from. It was another carman, Robert Paul, approaching. “Come and look over here,” said Cross, “there’s a woman lying on the pavement.”

They both crossed over to the body, and Cross took hold of the woman’s hands, which were cold and limp. Cross said, “I believe she is dead.” He touched her face, which felt warm. The other man, placing his hand on her heart, said “I think she is breathing, but very little if she is.” Paul suggested that they should give her a prop, but Cross refused to touch her. Neither witness noticed that her throat was cut, the night being very dark. The two men left the deceased, and in Baker’s-row they met a policeman, whom they informed that they had seen a woman lying in Buck’s-row. Cross said, “She looks to me to be either dead or drunk; but for my part I think she is dead.” The policeman said, “All right,” and then went to check on the deceased.

PC John Neil walked along Bucks Row at approximately 3.45am. He had passed the site thirty minutes earlier and noticed nothing out of the ordinary. This time he found the body, and with the aid of his lantern was able to examine the woman more closely than Paul and Cross had been able to do. He told the subsequent inquest into her death that: “Deceased was lying lengthways along the street, her left hand touching the gate. I examined the body by the aid of my lamp, and noticed blood oozing from a wound in the throat. She was lying on her back, with her clothes disarranged. I felt her arm, which was quite warm from the joints upwards. Her eyes were wide open. Her bonnet was off and lying at her side, close to the left hand.”

“I heard a constable passing Brady-street, so I called him. I did not whistle. I said to him, “Run at once for Dr. Llewellyn,” and, seeing another constable in Baker’s row, I sent him for the ambulance.”

“The doctor arrived in a very short time. I had, in the meantime, rung the bell at Essex Wharf, and asked if any disturbance had been heard. The reply was “No.” Sergeant Kirby came after, and he knocked. The doctor looked at the woman and then said, “Move her to the mortuary. She is dead, and I will make a further examination of her.” We placed her on the ambulance, and moved her to the Mortuary in Old Montague Street.”

“Inspector Spratley came to the mortuary, and while taking a description of the deceased turned up her clothes, and found that she was disembowelled. This had not been noticed by any of them before.”

This was Jack the Ripper’s first victim. She was Mary Ann Nicholls, a 43 year-old prostitute, who had been ‘put out’ from her lodging house about two hours earlier by the House Deputy, because she didn’t have the money to pay her rent. “I’ll soon get my doss money”, she laughed as she departed. “See what a jolly bonnet I’ve got now.” The house deputy said she was tipsy.

By Geoff Cooper

Recent Comments